By Akhil Suresh

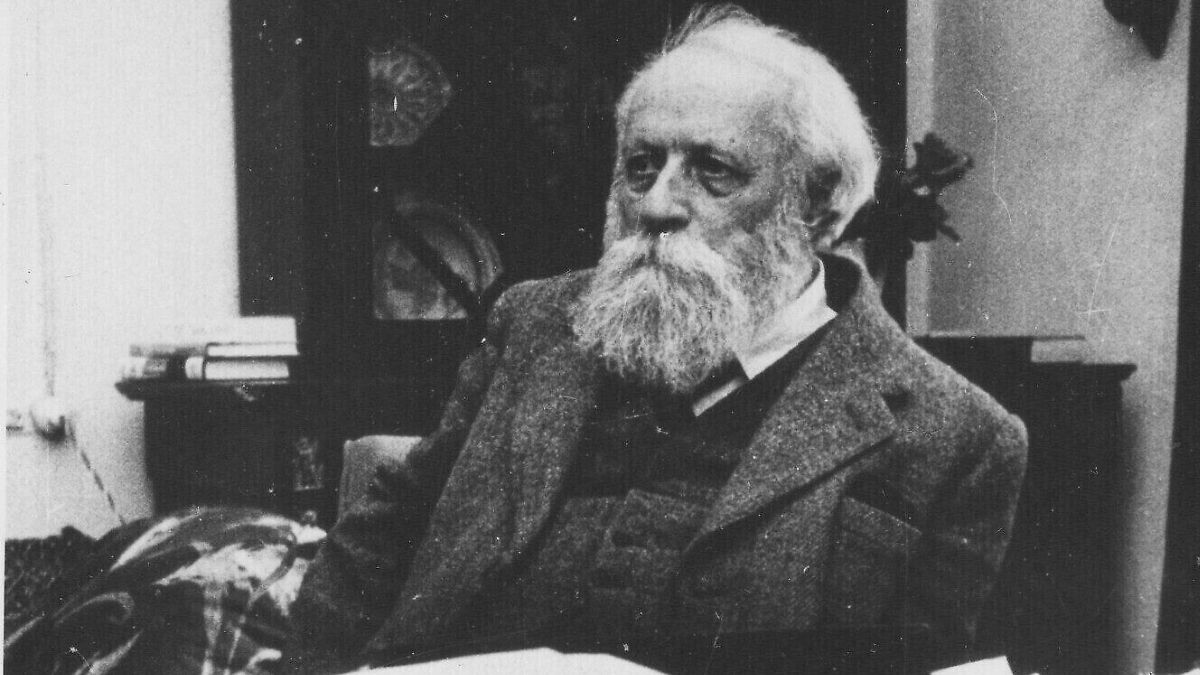

“It is Martin Buber, whose influence on modern thinking about dialogue overshadows almost all others.” says William Isaacs1 in the very first line of his article on the Action Theory of dialogue. Intrigued by Isaacs’ testimonial and a curiosity to understand an existentialist’s take on dialogue, I delved into the works of the Austrian-Israeli philosopher, the scope and focus of which ranged from philosophy, education, politics, conflict resolution, sociology, and mysticism. Having lived through some of the darkest chapters of European history including the rise of Nazism, Martin Buber2 witnessed first hand the dangers of dehumanisation and the importance of genuine connection between the beings of this world. He wasn’t just a philosopher who resorted to writing abstract concepts, but also a poetic author who believed in the profound wisdom held within stories. His works on dialogue are known to have a phenomenal impact on modern philosophy, theology, psychology, ontology, and communication studies.

Duality and Relations

Buber’s ‘philosophy of dialogue’ revolves around the duality of subjective experience. Human existence, in a Buberian perspective, is an ‘encounter’ between the self and his perceived world. This is essentially built around the relations a person has towards the different aspects of the world and an ultimate ‘God’, which is referred to as the ‘eternal Thou’. While Buber frequently employs the themes of God and mysticism in his discourses, he focuses on our relationship with God in exclusion to any attribution to the eternal being or other surrounding dogmas, appropriately placing his philosophy within the worldly realm of duality, while also keeping it away from the doctrines of religions. That is, the concept or idea of what God is, is not important. What is important on the other hand, is the perception of our relationship with it. In Buber’s words, spirit lies not in ‘I’ or ‘Thou’ but rather in between them- in the relation ‘I’ shares with ‘Thou’.3

Asakaviciute and Valatka4 point out how Buber classified the spheres of our relations into three: “the one with nature, with other men, and with intelligible forms.” By this approach, a relationship is not something shared invariably between two distinct entities: An individual’s thought, which is an intelligible form within him, can also be the other end of a relation he has. These relations continue to navigate our lives on earth with all other aspects such as feelings, ideas and meaning as mere accompaniments of the ‘fact’ of our relations. Our existence ceases in the absence of these relations. It would not be wrong to say that the experience of a mature human existence is nothing different from an infant’s innate tendency to establish and dwell in a relationship with its parent. All that changes throughout an individual’s life are the objects with which they share or yearn to share this relation. It is interesting to note how Jungian studies suggest that this notion of an overpowering idea of a collective relationship above all individualities can be traced back to the earliest understandings of the human psyche. 5

Dialogue and the ‘I-Thou’ relation6

Dialogue is identified as the force which drives this relational mode of existence. It is defined as an ‘existential encounter’ between entities through which relations develop and sustain.

Buber identifies two attitudes of existence through one of which, individuals relate to other entities. He termed them the ‘I-It’ and ‘I-Thou’ attitudes. The ‘I-It’ denotes an impersonal approach which treats other beings and things as objects. We categorise, analyse, and use them based on our needs. In an ‘I-Thou’ attitude on the other hand, there’s mutual recognition, respect, and a genuine meeting of minds. We approach the second entity as ‘Thou’ and see them as unique and valuable. We acknowledge their being and accept them with mutual respect and connection. Buber points out how, it is only in this attitude, dialogue thrives and relations sustain. Inversely, it is only through dialogue, the ‘I-Thou’ attitude thrives and relations sustain. ‘Thou’ affects the ‘I’ and ‘I’ affects the ‘Thou’, unlike what would happen in an ‘I-It’ relationship. Buber emphasises that the ‘Thou’ need not always be another person. A breathtaking sunset, a thought-provoking book, or even a challenging task is an object of relation. When we approach these ‘Thou’s with an open mind and a willingness to engage, we open ourselves to inclusion, growth, and the possibility of transformation. He identifies human relationship with God as the eternal ‘I-Thou’ relation and explains how each ‘I-Thou’ relation a person establishes with another entity drives him closer to the ultimate.

Neither modes of attitudes nor the types of relations are static in nature. Most encounters begin in an ‘I-It’ relation. It is ‘dialogue’ which transforms the ‘I-It’ into ‘I-Thou’. When you are buying stuff from a shopkeeper, waving at a taxi driver for a ride, or sitting on your balcony during a sunset, the other entity is just an ‘It’- an object of relation that happened to have crossed your path. But this changes the moment you engage with them. Acknowledging their being and approaching them as unique entities through dialogue, your relation transforms into ‘I-Thou’. Your relation with the sunset for example, transforms into ‘I-Thou’ the moment you observe its beauty and enjoy its serenity.

In the absence of genuine dialogue however, the ‘I-Thou’ may transform back into an ‘I-It’. While a certain number of ‘I-It’ relations are necessary for man to exist, it is the ‘I-Thou’ relations which help man find meaning in life. “Without ‘I-It’, man cannot live, but he who lives in ‘I-it’ alone, is not a man”- says Buber.

What does this imply?

Buber’s philosophy elegantly answers the questions that an individual may ponder while trying to make sense of the notion of dialogue. For instance, how can there be a dialogue or relation if the interests of multiple entities collide? It is when interests collide that dialogue becomes more crucial. It is through dialogue the other entity is validated and their interests get acknowledged. The entities with colliding interests can accept the possibility of not getting exactly what they want while still valuing the relationship through an ‘I-Thou’ approach. This may lead to stronger bonds and personal growth. A more significant insight would be that the maintenance of this ‘I-Thou’ approach should always stay highest in the hierarchy of interests of an individual. This is because it is not just a method to build acquaintance or collaboration but it also is what drives our existence as human beings in this world.

Consider another question: What if an individual hates another? How then can dialogue be possible with the other? “Hate by nature is blind,” answers Buber. He explains how only a part of an individual can be hated. An individual who sees a whole being and approaches it with an attitude of ‘I-Thou’ is no longer in the ‘kingdom of hate’. They are in the kingdom of existence, which involves a constant affirmation of the other entity’s being. Although hate might be the beginning of a relationship, it ceases to endure as dialogue thrives. The entering into a relationship recognizes the relativity of that relationship, and consequently the barriers to that relationship are reduced. Thus, “a man who straightforwardly hates is nearer than a man who neither hates nor loves”.

While Buber’s philosophy focuses on enhancing humankind’s construal of existence through dialogue, it does not venture to define dialogue in terms of a well-structured framework or a practical model for application. The modern world, with its constant burden of information overload and projected personas presents several challenges that hinders genuine dialogue and relations. This is where the Dialogic Method comes into play. By intertwining the timeless wisdom of Buberian philosophy with the practicalities of our daily lives, the Dialogic Method acts as a map, helping us easily approach the world and all its components as our most beloved ‘Thou’.

- William N. Isaacs bisaacs@mit.edu (2001) TOWARD AN ACTION THEORY OF DIALOGUE, International Journal of Public Administration, 24:7-8, 709-748, DOI: 10.1081/PAD-100104771 ↩︎

- Zank, Michael and Zachary Braiterman (2023), “Martin Buber”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.) ↩︎

- Buber, M. (2008). I and Thou. Howard Books. ↩︎

- Asakaviciute, Vaida & Valatka, Vytis. (2020). Martin Buber’s Dialogical Communication: Life as an Existential Dialogue. Filosofija. Sociologija. 31. 10.6001/fil-soc.v31i1.4178. ↩︎

- Jung, C.G. (1923). Psychological types: or the psychology of individuation. Harcourt, Brace. ↩︎

- See footnote 3

Image citation : Mendes-Flohr, N. (2018). Childhood trauma may have led to Martin Buber’s cerebral trust in higher power. Times of Israel. ↩︎